How can your city’s land use prepare it for downturns?

Financial Principles for Building Municipal Wealth: Part 3 — Prepare for Downturns

Last week, I discussed how cities must

prioritize their needs over wants. The week before that, I explored how cities can

live within their means

by building less infrastructure. This week, we are examining how different land use patterns can either reduce or increase your city’s resilience against economic downturns.

Growth can be a great thing for city finances. With growth comes an inflow of cash from more businesses, more people, more investments, and higher land values. That cash can then be used to fund projects across the city that improve residents' lives.

But what happens when that growth slows or stops altogether? A downturn in the housing market, a factory closure, or a sudden drop in sales tax revenue (during a pandemic, for example) can bring city budgets under stress.

When that happens — not if, when, because it will happen eventually — can your city still meet its obligations to taxpayers and lenders? The answer often depends on land use decisions made years earlier.

Maintenance is forever

Infrastructure is expensive to build, but cities have many ways to make the cost burden lighter: impact fees, developer agreements, tax-increment financing, et cetera.

However, once infrastructure is built, a city is responsible for maintaining that infrastructure as long as it and the city both exist. Those costs include routine annual maintenance tasks like filling potholes and street cleaning, as well as infrequent, large-scale maintenance projects like resurfacing and reconstruction.

Keeping up with these costs is much harder, and funding options are often limited to local taxes and service fees. That said, a city’s tax base must be strong enough to pay for annual maintenance expenses, reserve funds for future maintenance costs, and pay for other essential services.

This is impossible if properties are not producing enough tax revenue to cover the costs of the infrastructure they use and then some.

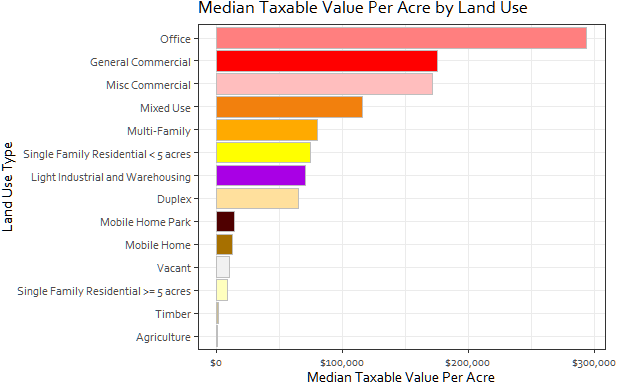

High-density or mixed-use neighborhoods, commercial centers, and industrial parks can pull this off, especially when they are built around existing infrastructure. Low-density, single-family neighborhoods rarely do, yet they constitute the majority of our city’s developed land.

In a high-growth scenario, this matters less because the influx of cash from other sources offsets many of the uncovered costs. However, in a downturn, sufficient property tax revenue and reserve funds are critical to preventing service cuts.

Flexibility creates resilience

Beyond property values and reserve funds, land use flexibility is also critical to surviving downturns.

When zoning allows for more density and mixed uses, it gives residents and businesses room to adapt. For example, a single-family home can be converted to a duplex, an underutilized parking lot can become a farmers’ market, or a garage can be used to start a home business.

These changes may be small, but they are powerful. They help stabilize neighborhoods by supporting local entrepreneurship, providing more housing, and reducing vacancies, often without requiring significant public investment.

The more rigid a zoning code is, the less responsive individuals and communities can be to changing economic conditions.

Conclusion

Cities can’t avoid economic downturns, but they can choose to prepare for them. That preparation begins with land use plans that prioritize fiscal responsibility and flexibility.

By allowing financially productive developments on existing infrastructure and enabling neighborhoods to adapt over time, cities can build the financial resilience needed to weather hard times without cutting essential services.

The next downturn will come. It’s just a matter of when. Cities that plan accordingly will be ready.

If you would like additional guidance with your community’s land use plan, schedule a consultation with us today!